Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) is the leading cause of dementia, and its prevalence is increasing along with standard life expectancy. This is a serious public health concern, which I had the opportunity to read about as apart of my Neurology rotation.

Alzheimers is a currently incurable neurodegenerative disease, characterized by accumulation of amyloid beta plaques and neurofibrillary tangles of hyperphosphorylated tau proteins.

These processes likely lead to neuronal death, cognitive decline, and memory loss, which are the key clinical features of this chronic, progressive illness. Risk factors include older age, social factors such as education level and economic status, family history, gene mutations, oxidative damage, and neuroinflammation, among others.

Research focusing on various pharmacologic interventions in the process of amyloid production and accumulation has so far proven unsuccessful. Research is now focusing more on tau, but these efforts have also fallen short of finding a cure. From a prevention standpoint, there has been significant interest in the modifiable lifestyle risk factors associated with AD, such as diet and exercise. In this article I will present some of the recent findings related to dietary interventions found to potentially decrease risk of Alzheimer’s. We will break down a few specific diet plans, review current research, and then highlight some key nutrients thought to play a role.

Dietary interventions are difficult to study because people generally do not eat food groups in isolation, and when a certain health effect is linked to a certain food, there are infinite combinations of nutritional elements and psychosocial factors that may be at play. That said, there are a growing number of studies which investigate connections between diet and cognitive decline in meaningful ways.

Of the diets that have been studied, three or four in particular stand out. First, the ketogenic diet. This diet is high in fat and low in carbohydrate and medium-chain triglycerides. The idea for this one is to get the body into ketosis so that the brain will use ketone bodies instead of glucose. This diet is often successful in treating refractory childhood epilepsy, but it has been studied for a possible intervention for cognitive decline as well. The premise for the connection here is that glucose metabolism in the brain is closely related to neuroinflammation. PET imaging also reveals a decline of glucose metabolism in early AD but no decrease in ketone use. A 2020 translational review of 11 human and 11 animal studies showed that this might be a promising way of altering cognitive symptoms in the prodromal stage of Alzheimers. However, even though it is often associated with weight loss, there are concerns about adverse cardiovascular effects associated with the high intake of saturated fats from animal sources. More research is needed in this area, as it specifically relates to brain health.

We will look at the next two diet plans together because they are related: The Mediterranean Diet and the DASH Diet.

Both of these two diets are predominantly plant-based: high in whole grains, legumes, nuts, seeds, fruits and vegetables, and low in things like red meat and highly processed foods. The mediterranean diet is also high in “good fats” like olive oil and fish, as well as a moderate amount of wine, whereas the DASH diet includes low-fat dairy products, and lower amounts of fish and does not include alcohol. Both of these diets have been connected with improved cognition in older adults in observational and epidemiological studies, and have thus warranted a closer look into diet as a deterrent to cognitive decline in older age.

On molecular and cellular levels, there are distinct nutrients linked with the observed benefits of each of these diets. The mechanisms involved here are separate from the better understood vascular effects, and center around reducing inflammation, improving cellular support through processes like oxidation of free radicals and maintenance of cell membranes, and various related epigenetic mechanisms. We will look more specifically at some of those key components in just a moment.

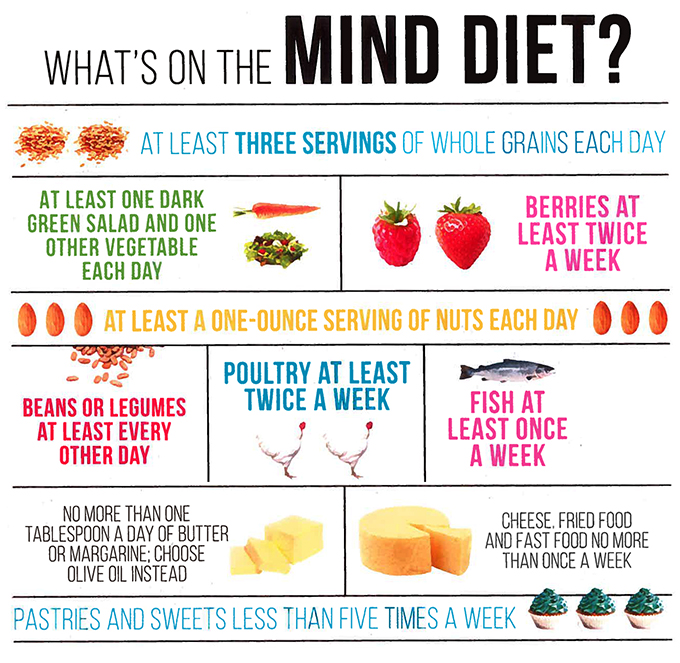

The MIND diet was developed in 1997 as a hybrid of the Mediterranean diet and the DASH diet, combining principles of each of those, specifically focusing on key nutrients that have been connected to the benefits of each of these diets on slowing cognitive decline. This diet is in keeping with dietary guidelines that we already associate with a “healthy diet”: more fruits, vegetables, lean proteins, healthy fats and whole grains, and less saturated fats and sugar. But the MIND diet specifically emphasizes the addition of berries and leafy green vegetables, as well as the inclusion of fish at least once per week, and small quantities of wine.

In a prospective study, published in 2015, the MIND diet was compared to the DASH and Mediterranean diets. Each study group was asked to adhere to one of the three diets and then scored on their reported adherence. Participants were assessed regularly using intense cognition & memory testing. In an adjusted proportional hazards model, both moderate and strong adherence to the MIND diet were associated with lower AD rates, whereas only strong adherence to the DASH and Mediterranean diets showed cognitive benefit.

There have been 5 longitudinal prospective studies and 1 cross-sectional study over the past five years. After adjusting for other variables, adherence to the MIND diet consistently shows a linear and statistically significant relationship with reduced risk for cognitive decline. Links have been demonstrated between the MIND diet and lower risk of mild cognitive impairment and dementia; reduced risk of Alzheimer’s disease, and slower decline in global cognition in multiple domains listed here. There have been a handful of meta-analyses and systematic reviews, but it is nearly impossible to condense the data because each trial uses a slightly different description of the diet and assesses unique sets of endpoints.

That said, these observational studies rely on self-reporting of participants’ dietary intake, often by elderly patients, which likely introduces reporting bias as well as recall bias. As observational longitudinal studies, participants typically have a choice in their level of adherence to the prescribed diets. Participants with higher levels of education, higher incomes, and higher exercise levels were more likely to adhere to the recommended diet plan. Any of those variables may have contributed to their outcomes. More research is needed to evaluate the effects of this diet plan in more subgroups within the population.

The specific nutrients involved have been studied separately, with mixed results. Of key interest are:

- Omega 3 polyunsaturated fatty acids, which are found in nuts, fish, and olive oil.

- These have been shown to lower risk of dementia in individuals without cognitive impairment, but results have been mixed in clinical trials of individuals already showing decline. Dietary fish intake has been shown to possibly slow progression of cognitive decline, but taking fish oil supplements shows little to no significant impact.

- Flavonoids, which are natural compounds found in vegetables, grains, roots, flowers, tea, wine, and coffee, which have antioxidative, anti-inflammatory, anti-mutagenic, and anticarcinogenic properties, and have been shown to influence epigenetic processes: down-regulating inflammatory biomarkers and reducing expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines.

- Minerals such as calcium, magnesium, and potassium, which are involved in numerous cellular processes related to cognitive decline and have all been shown to have protective effects

- Vitamins, particularly B-12 and folate, on which there are very few clinical trials, showing mixed results

- Lastly Resveratrol, which is a polyphenol found in grapes and red wine. Resveratrol has strong antioxidant and anti-inflammatory actions. It binds several biomolecules and activates sirtuin 1 and class III HDAC, protecting cells against inflammation and oxidative damage

- Curcurmin, the active compound in turmeric, is another compound that significantly modulates epigenetic control, downregulating expression of Class I HDACs and upregulating acetylated histone H4 levels in Raji cells (a line of human cells of hematopoietic origin, used in transfection experiments)

In summary, while the existing literature on the MIND diet supports recommendations for lifestyle approaches to reducing risk of cognitive decline and Alzheimer’s disease, but cause and effect cannot be known for sure, as this is a complex and multifactorial illness. Future directions for studying the MIND diet should be focused on specific food components and combinations and their mechanisms of actions, to determine effective serving sizes and to allow for minor, realistic dietary changes people can begin to implement.

Disclaimer: I am a medical student and am not yet licensed to provide medical care. This article is intended as a review of current research on a topic I find interesting. Please consult your primary care provider for personalized advice on incorporating dietary changes into your lifestyle.

Resources

Bhatti GK, Reddy AP, Reddy PH, Bhatti JS. Lifestyle Modifications and Nutritional Interventions in Aging-Associated Cognitive Decline and Alzheimers Disease. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience. 2020;11. doi:10.338%fnagi.2019.00369

Cummings J, Lee G, Ritter A Zhong K. Alzheimer’s Disease Drug Development Pipeline: 2018. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2018;4:195-214. doi:10.1016/j.trci.2018.03.009

Hosking DE, Eramudugoilia R, Anstey KJ, [P4-363]: The Mind Diet Is Associated with Reduced Incidence Of 12-Year Cognitive Impairment in An Austrailian Setting. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2017;13[75_Part_29]. doi:10.1016/j.jalz.2017.06.2234.

Lilamand M, Porte B, Cognat E, et al. Are ketogenic diets promising for Alzheimer’s disease? A translational review. Alzheimer’s Research & Therapy. 2020;12:42. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13195-020-00615-4

Lourida I, Soni M, Thompson-Coon J, et al. Mediterranean Diet, Cognitive Function, and Dementia. Epidemiology. 2013;24(4):479-489. doi:10.1097/ede.0b013e3182944410.

Psaltapoulou T, Sergentanis TN, Panagiotakos DB, et al. Mediterranean Diet, Stroke, Cognitive Impairment, and Depression: A Meta-Analysis. Annals of Neurology. 2013;74[4]. https://doi-org.ezproxy2.library.drexel.edu/10.1002/ama.23944.